The Marine Resources Department (DRM) and pearl farmers from Mangareva have carried out a pearl oyster reintroduction operation in the Gambier lagoon—a key initiative to revitalize the region’s pearl farming sector.

Facing a decline in pearl oyster spat collection, an essential element for oyster production, this operation aims to restore oyster populations and strengthen local pearl output.

Operation Details

During this two-day effort, a total of 3,500 mature pearl oysters were reseeded in specific sites identified by researchers from IRD and Ifremer. These adult oysters will serve as a foundation for future reproduction, with the hope that their reintroduction will stimulate natural spawning in the lagoon.

James Gooding, a local pearl farmer, emphasized that this initiative is not just an ecological gesture but also a way to raise awareness among farmers about environmental challenges and strengthen community cooperation. He added that if successful, additional reintroductions could be considered in the future.

Economic and Symbolic Importance

The Tahitian pearl remains an economic cornerstone for French Polynesia, accounting for 70% of local exports. The Gambier Islands, in particular, play a major role in this industry, contributing around 33% of the territory’s total pearl production.

What sets Polynesian pearl farming apart is that oysters are cultivated directly in the wild, unlike in other producer countries (such as Indonesia, Myanmar, or the Philippines), where hatcheries are used.

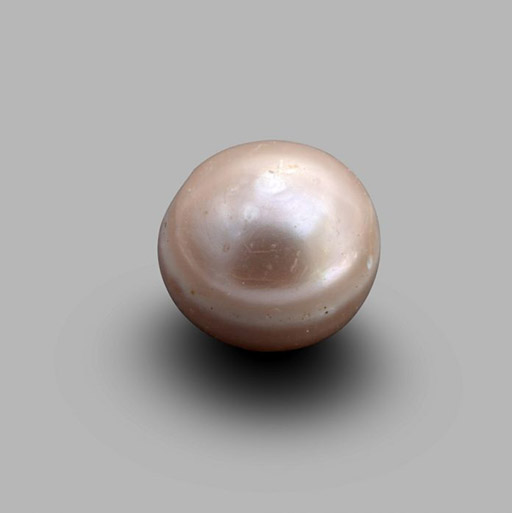

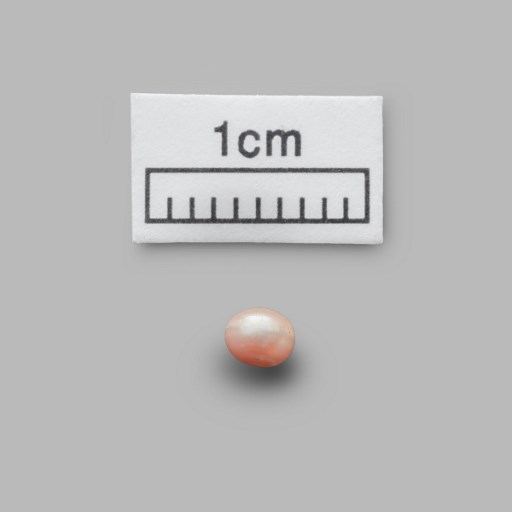

Oysters are placed on ropes in the lagoon for about six months, where they feed and grow before being harvested. This natural method not only produces unique pearls but is also considered more environmentally sustainable.

Future Goals

This reintroduction aims to ensure the long-term sustainability of the pearl industry while restoring the health of local marine ecosystems. Pearl farmers in the region continue to monitor the reintroduced oysters and hope they will enhance the resilience of pearl production against future ecological and economic challenges.